Something people tend to ignore about the high price of child care in the United States is that it’s not just a burden on individual families; it’s really a weight on our entire economy.

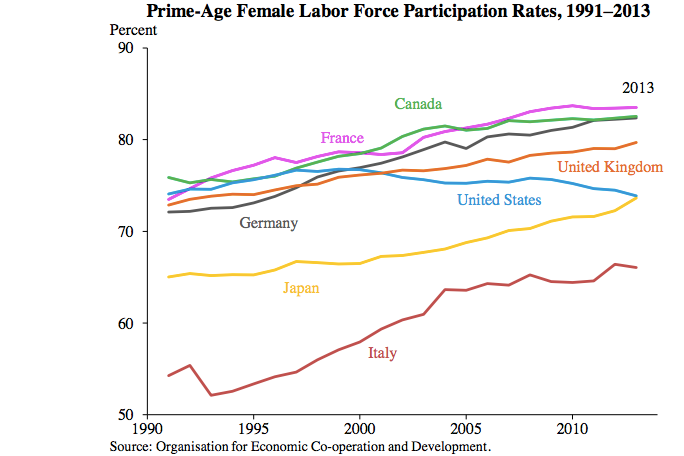

The drag is obvious if you look at how female employment has stalled in the U.S. compared with the rest of the globe since the early 1990s. Back then, shoulder pads were in, Murphy Brown and Designing Women were on the air, and the share of American women in the workforce was reasonably high by global standards. We trailed Nordic nations like Finland and Denmark, which have long, progressive track records on gender norms and family policies. But we were at least in the same ballpark as countries like France, Germany, and Canada, and in some cases outright ahead of them.

Over time, though, the U.S. fell far behind. American women’s labor force participation peaked in the year 2000, then declined. In other wealthy countries, it continued to rise.

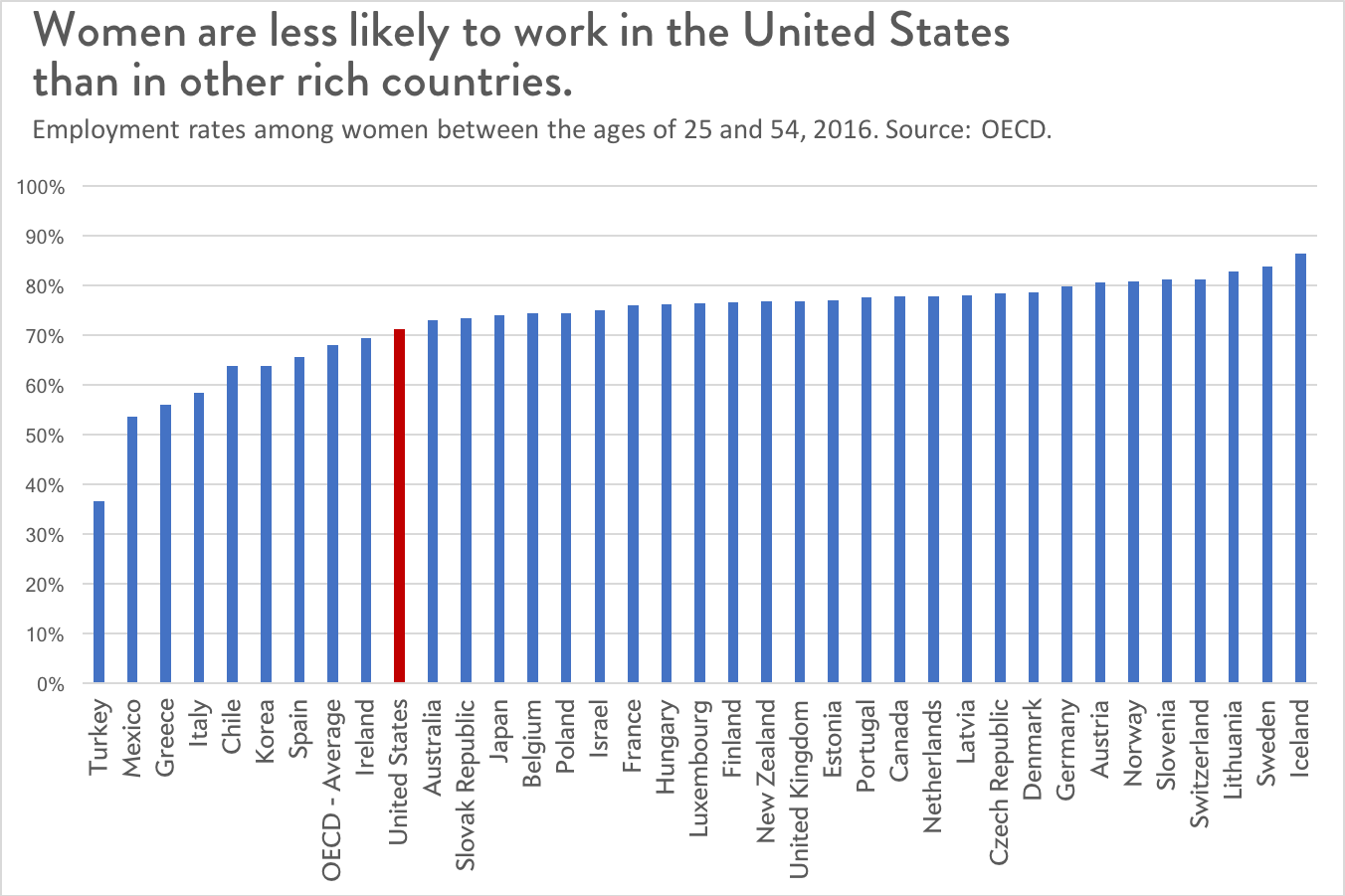

Today, the U.S. doesn’t simply lag Western Europe on this measure. We’re behind most of the developed word. Our country ranks 28th out of 36 in the OECD when it comes to employment among women between the ages of 25 and 54 (which are generally considered a person’s prime working years). Forget Scandinavia. We’re underperforming economic also-rans like Poland and Latvia, as well as socially conservative Japan, where the culture has traditionally emphasized a mother’s role in the home.

Why did American women stop storming the job market? Much of the fault lies with our archaic family policies. Other countries took steps to ensure more mothers could work. They expanded paid family leave—which tends to anchor women in the labor force—and offered more generous child care. Japan’s almost miraculous-seeming progress was aided by shifting social norms and an official crackdown on workforce discrimination. In the U.S., however, our approach to supporting parents stayed frozen in time. We remain the only developed nation that doesn’t guarantee paid maternity leave, and day care can now cost as much college tuition. In effect, we’ve placed a ceiling on the share of women who can realistically work. In one well-known paper, economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn estimated that if the U.S. had even an average set of family support policies compared to the rest of the world, women’s labor force participation would be almost 7 percentage points higher.

Of course, many, many women choose to stay home with their kids, or only work part time, because it’s what they prefer. In 2012, only 32 percent of mothers with children under 18 said they would ideally like to work full time. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with wanting to spend a few years exclusively caring for your infant or toddler. That’s what having a free choice between work and family is all about.

But for many mothers, it’s not much of a free choice. Some are nudged out by the cost of day care, which makes working seem less financially worthwhile. This is bad for individual women and bad for the broader goal of gender equality. The years of experience mothers lose while staying home with children can have a deadening impact on their long-term earning power, which goes a good way toward explaining the persistence and severity of the gender pay gap in this country.

And it’s also bad for our economy. In the end, GDP growth boils down to a pretty simple formula. It’s labor force growth plus productivity growth—that’s all. And by limiting the share of women who are able to work, we’re limiting the size of our labor force. We’re straitjacketing the economy.

This fact tends to get short shrift when people write about child care policy. In her great New York Times op-ed over the weekend calling on 2020 candidates to embrace universal child care, for instance, Katha Pollitt pointed out that the expense of day care forces some women out of their jobs, but she never connected it to America’s broader economic prospects.* That’s not especially surprising. For most Americans, the sheer cost of finding a decent place to look after your toddler while you work is a much graver, more visceral concern than abstractions about GDP growth. But it’s an unfortunate omission. One of the better arguments for providing child care services—as opposed to straight cash payments to parents, as some policy wonks have proposed—is that encouraging women to stay in the workforce will create future economic gains.

There are also some people who will argue that helping women to stay in the workforce, rather than stay home with their children, would mostly improve growth on paper, without necessarily improving our real economic well-being. The basic idea is that a mother caring for her own child is doing unpaid labor that creates real economic value, even if its precise market worth is hard to measure. This notion relates to an ongoing and important discussion about how accurately concepts like gross domestic product actually gauge the economy’s productive capacity or our national quality of life. But the bottom line is that there are probably gains to be had from helping women who want to work outside the home do so, and reserving more child care for professional centers that can do it a bit more efficiently. (Even if you factor in rent and other overhead, it’s probably more cost-effective for one caretaker to watch over four infants than it is to have every parent looking after their own.)

How big could those gains be? One popular figure comes from a Strategy& analysis from 2012, which suggested that the United States could increase the size of its economy by 5 percent if women’s labor force participation rose to match men’s.* That isn’t likely to happen any time soon, but it suggests that as a country, we are clearly leaving GDP points on the table.

American politics has a deeply embedded sexist streak, and family policies—such as child care and paid leave—have traditionally been treated as softer, second-tier concerns, in part because they’ve been seen as “women’s issues.” That’s thankfully beginning to change, as more men realize that parenting is their role as well, and that two incomes are really necessary to maintain a stable, middle-class household. But politicians should also realize that providing affordable child care and helping women who want to stay at work may be one of the simplest, most straightforward ways we can boost growth. Until they do, our economy will keep paying a price for the price of day care.

Correction, Feb. 12, 2019: An earlier version of this article misidentified Strategy&, formerly known as Booz & Company. This piece also originally misspelled Katha Pollitt’s last name.